Lindsay Digweed 29th December 2020

Key words: resilience, sport, youth sport, youth athlete, sport psychology, coach-athlete relationship, positive training environment

“I’ve failed over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.”

– Michael Jordan

Many children participate in sport, with some eventually reaching high performance status. But how do they get there? What separates them from the athletes who don’t make it? A big part of this is resilience. Read on for practical advice on building resilience in your athletes.

After reading this blog, as a coach you should be able to:

- Identify traits of resilience in your athletes

- Be able to explain to athletes, colleagues and parents what resilience is, what it is useful for and how we can develop it

- Be able to give your athletes the mental skills needed to become more resilient

- Identify how to improve your coach-athlete relationships to help athletes become more resilient

- Create a training environment favourable to both skill development and resilience building

Definitions

“The capacity of individuals to cope successfully with significant change, adversity or risk” 1

If you look up resilience in research, you will come across a variety of definitions. However, they all include some form of positive adaptation to adversity 2. Responding resiliently requires an array of life skills, problem solving and utilising social support to positively adapt to stress which leads to better mental and emotional well-being 3. It is important to remember in a sporting context that positive situations can also require resilience – athletes need to be able to maintain focus and not become complacent when they are winning, and they need to be able to manage the pressure of staying at the top when they get there 4. Participation in sport has been found to increase self-esteem and resilience 5.

Resilience in life

Everyone experiences adversity at some point in their life, whether it be struggling in school, relationship breakdown, losing a job or the death of a loved one. Resilience is a life skill, and if we can train children to be resilient now, they will be more successful as adults. In fact, resilience is a hot topic in business, with many companies listing it as a desirable attribute for interview candidates. People with high levels of resilience are usually more optimistic and less likely to suffer from anxiety and depression 6.

Resilience in high performance sport

High performance sport is stressful. There are high expectations placed on athletes from themselves, family members, coaches, governing bodies, fans, the media as well as having sponsorships and endorsements riding on success at sporting events. To be successful at the highest level, athletes need to be able to handle their emotions under enormous stress 7. Olympic champions tend to be higher in resilience, confidence, focus, optimism and have a strong work-ethic 8. Athletes measuring higher in resilience are more likely to successfully make the move to professional sport 9. In fact, 82% of wrestling coaches rate mental toughness as the most important psychological attribute for success, especially at higher levels 10. Mental toughness is a concept involving self-determination, motivation and most importantly resilience. For a more in-depth discussion on this specific attribute please see Weinberg, Butt & Culp 11.

In some sports peak performance occurs during adolescence, for example in women’s artistic gymnastics the peak age is 13-14 years 12. For these athletes, managing the pressure of elite sport alongside schoolwork, friendships, developing bodies and raging hormones requires a lot of support. It is important for you, as a coach, to remember that athletes are only human and can’t possibly be resilient to every single stressor they encounter, especially for youth athletes who are still developing their resilience. Therefore, it is important you are able to give your athletes the tools to increase their resilience and to monitor when this becomes too much.

During her first tumbling competition, one of my athletes managed to forget how to count! [resulting in a zero score] As she stepped off the track, she looked to me for a cue on how to react. I smiled at her, gave her a big hug, and said “I’m so proud of you”

If you coach a team sport you will need to not only develop individual athlete’s resilience but also work on team resilience as a whole. Developing team resilience is beyond the scope of this blog, for further discussion on this topic please see work by Morgan, Fletcher and Sarkar 13; 14.

Burnout

Children who participate in youth sport experience a range of benefits including better behaviour, attendance and grades in school as well as improved self-confidence 7. The self-discipline learnt through sport has also been shown to transfer to conflicts outside of sport 15. Burnout occurs when the demands on a person outweigh their psychological resources to manage these demands, therefore those measuring higher in resilience are less prone to burnout. Once burnout occurs it is similar to depression and seeps into all areas of life 16. Youth athletes have more demands on them than non-athletes, so it is important we use sport to teach them resilience skills. It is also important to be aware of other areas of athlete’s lives’ where pressure may be high to prevent burnout from this domain affecting their performance in their sport.

Stressors 6

Stressors may be separated in to personal, competitive, and organisational, some examples are listed below.

Personal: academic commitments, family issues, death of a loved one, relationship breakdown

Competitive: fear of injury, actual injury, return to training following injury, slow progression, poor personal and team performances, making mistakes, performance expectations from themselves and others, not wanting to let coaches and teammates down, competing in front of large audiences or on television, rivalry with other athletes

Organisational: leadership issues, team atmosphere and support, facilities and equipment, weather conditions, travel and accommodation, team selection.

- Organisational stressors are strongly linked to burnout and are experienced more often by elite performers 17.

ATHLETES

Identifying traits of resilience in your athletes 18

Resilience is both a personality trait and a psychological skill. This means we all have an innate level of resilience. So what personality characteristics are linked to resilience?

- Extraverted/outgoing

- Self-confident

- Conscientious

- Optimistic

- High personal standards

- Not overly dramatic/emotional

- Competitive

- Proactive

- Inherently enjoys the activity

- Both ego and task oriented – a desire to be better than others but also better than themselves

- Self-serving attributional style – attribute success to their own abilities or effort but failure to external factors

Psychological Skills 18

Personality characteristics are relatively set. However, with training, we can increase our athlete’s levels of resilience by teaching them psychological skills.

- Awareness: Using training and competition diaries can help athletes learn from their mistakes and failures as well as their successes 19

- Pre-performance routines: specific to the athlete, may be a physical action such as practicing a tennis serve or mental such as self-talk or mental rehearsal (see below)

- Self-talk: teach your athletes to verbalise whatever they need to focus on, this can be done out loud or in their head. It can be an instruction to focus on such as “hit the ball straight” or motivational such as “I’ve got this”

- Mental rehearsal: the athlete remembers or imagines the desired behaviour e.g., performing a skill, a routine or winning a match. For maximum effect they should try to use all their senses

- Attentional control: By introducing distractions during training, you can desensitise your athletes to distractions they may encounter on the competition floor or field of play (see pressure inurement training below)

- Arousal regulation: slow breathing techniques & body relaxation to calm the body, panting & body arousal techniques to ‘pump up’ depending on the athlete’s needs

- Goal setting: goal setting should be done regularly with small, achievable goals. Goals need to be realistic and maintain perspective on the bigger picture

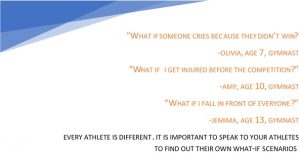

- What if scenario analysis/black swan event response: Consider all possible scenarios, talk through the what-ifs with your athlete. Allow them to consider the least likely and worst-case scenarios and discuss what this would mean for them or how we can prevent these from happening. Anything from the car breaking down on the way there, illness, injury and what happens if they lose.

Challenge mindset 18

“When I was in grade school, I was diagnosed with…ADHD. I had overcome that. When I was in school, a teacher said I’d never be successful. Things like that stick with you and motivate you”

-Michael Phelps 20

When people are faced with a situation, we either evaluate it as a threat or a challenge 21; 22. To be resilient athletes need to learn to assess situations as challenges rather than threats. To do this we need to address the athlete’s negative thinking patterns:

- Awareness: Make athletes aware of their negative thoughts and the fact that they have power over their thought processes.

- Negative thinking patterns include:

- ‘end of the world’ thinking: catastrophic thinking

- ‘it can’t be done’ thinking: pessimistic beliefs about the future

- ‘it has to be perfect’ thinking: believing mistakes equal failure

- Negative thinking patterns include:

- Regulating thoughts: when a negative thinking pattern is identified the athlete needs to

- Stop

- Verbalise thoughts or write them down

- Confront them by challenging their irrationality

- Then replace them with positive or constructive thoughts

By helping our athletes achieve a challenge mindset as well as giving them mental skills training, we can build strong athletes who are resilient enough to reach high performance standards.

COACHES

Communication

According to NCAA division I coaches, establishing positive coach-athlete relationships and a strong culture within the team are the most important elements for developing mental toughness 23. How you communicate with your athletes has a massive impact on their development. Strong, trusting relationships offer support to athletes which aids resilience. In fact, a close relationship with an adult outside the family is beneficial for at risk adolescents 24. Autonomy support is also beneficial, helping your athletes to feel more competent as well as resulting in better sportsmanship and higher motivation and effort 25; 26.

- Display confidence in your athletes: when your athlete feels that you display confidence in them, they are more resilient 27.

- Supportive communication: e.g., praise, provides emotional support and increases self-efficacy 5.

- Being overly tough and negative to encourage athletes to work hard has unfortunately been a common practice in youth sport 26

- Constructive criticism: this needs to be informative feedback to improve skills whilst remaining positive and encouraging. Athletes will be more receptive when they have a trusting relationship with you 28

I distinctly remember attending a rugby match for my son who was probably only 9 years old at the time. The coach for the opposing team shouted at his players constantly. There was no positive encouragement or praise, just anger when they failed to score tries. At one point he knelt down to scream in a child’s face, he even screamed at a parent who dared to talk to him! It wasn’t a pleasant experience. I left the match so grateful for my son’s own coaches who have always been positive and encouraging.

- Active listening: this shows the speaker you are listening and fosters feelings of connectedness to build a trusting relationship

- nonverbal communication such as eye contact and nodding

- Giving appropriate feedback on all information

- Paraphrasing

- Asking open ended questions

- Being empathetic

- Acknowledging the speaker’s feelings

- Make it fun: Sport should be fun. Humour is a helpful coping mechanism and can help provide a positive experience that enables your athlete to form a love for the sport before the seriousness of competition catches up with them. By creating a fun, friendly environment in training you can develop rapport and strong relationships with your athletes 29

- Autonomy support: involve your athletes in their own development process and give them choices where possible. When an athlete feels as though you trust their decision making, they are more confident which can help them makes decisions when under stress 26

- Recognise athletes as individuals: If you are working with a new group of athletes why not ask them to write down three things they want you to know about them to get to know them better 26

- Consider peer relationships: Athletes with strong peer relationships have higher self-esteem and are more resilient 30. However, in discussion groups it is important to remember that adolescents can be particularly self-conscious so using smaller groups is better 31.

- Language: remember they are children! Especially younger children need simple language and concrete concepts. They require repetitive explanation and shorter sessions on psychological skills – ideally this will be incorporated into physical skills training 31.

Excellent communication skills are vital for coaches to develop positive coach-athlete relationships and to support their athletes to high performance.

ENVIRONMENT

Both male and female athletes benefit from a warm and friendly training atmosphere which can help them to manage stress, even when that stress comes from outside sources 5.

Mastery climate 32

The environment your athletes train in can have either a mastery- or performance-oriented motivational climate. Mastery climates are linked to higher resilience, confidence, feelings of competence, and lower burnout 33. A mastery climate focuses on individual improvement and values effort, failure is considered part of the learning process. A performance climate values competition and beating others. Athletes work to set time scales and standardised goals where mistakes are considered failures. An athlete’s self-worth relies upon their ability to perform a performance goal.

The TARGET model 34 can be used to develop a mastery climate.

Tasks: must be challenging and varied to maintain engagement.

Authority: Athletes should be involved in decision making and given opportunities for leadership. Coaches should avoid a ‘do-as-I-say’ mentality.

Recognition: Athletes should be privately recognised and praised for their effort and personal improvement.

Grouping: Athletes should be grouped based on cooperative learning rather than ability*

Evaluation: Focusing on effort and personal improvement rather than winning or comparison against others**

Time: allow for enough time to practice and complete tasks dependent on the individual

*Some sports typically use age groupings whereas some use ability groupings. For sports that typically work with ability groupings it is still possible to achieve this by varying who athletes work with each week within their group.

**whilst this can’t be avoided in competitions and matches you should not highlight differences between athletes in class or use them for either praise or punishment.

Facilitative environment 18

To get the best out of your athletes you need to provide a facilitative environment. By providing challenge to your athletes, you are able to stretch them outside of their comfort zone whilst providing developmental feedback. A high challenge environment provides high expectations and gives your athlete responsibility for their own performance. By providing support to your athletes, you can help them to achieve their goals and provide encouragement through motivational feedback. A high support environment builds trust between you and your athlete and aids learning. When you can provide an environment that effectively balances challenge and support this provides the ideal environment for both skill and resilience development. By providing too much or not enough of either challenge or support, different environments are created that are not beneficial to progress.

Pressure inurement training 18

In order to provide the necessary challenge, you will need to manipulate the training environment. Pressure inurement training does this to the point where a stress-related response can be seen in the athlete. Pressure inurement training is regularly used by many coaches, even without knowing they are doing it! To create pressure inurement training:

- Create a challenge to push your athlete out of their comfort zone – this may be attempting a new skill, performing in front of others, or being given more responsibility within a team.

- Carefully monitor how your athlete responds to this challenge:

- If your athlete demonstrates negative responses, you will need to provide more motivational feedback and support. If this does not work the challenge may need to be decreased.

- If your athlete demonstrates positive responses either your athlete has adapted to the challenge or the challenge was not great enough. You can now increase developmental feedback as well as increase the challenge further.

By creating a mastery climate and a facilitative environment coaches provide the best possible atmosphere for talent development.

Take home messages

- Athletes, like all people, face adversity in their lives that require resilience in order to adapt positively

- Resilience is extremely important for high performance athletes. However, as resilience is an important life skill this training is beneficial to all athletes

- There are many traits athletes may already possess that predispose them to being more resilient; by introducing psychological skills training to your programme, you can build upon these to make your athletes even more resilient

- The nature of the coach-athlete relationship is crucial; coaches must develop a strong, trusting relationship with their athletes to build strong, resilient athletes

- By creating a mastery climate and a facilitative training environment, athletes will be in the best position for both skill development and resilience building

Are you a coach working with youth athletes? Are you an athlete who has experienced positive or negative coaching in your career? Tell us about your experiences below!

Don’t forget, if you like this article, share it with your friends and colleagues!

References

-

Lee, H. H., & Cranford, J. A. (2008). Does resilience moderate the associations between parental problem drinking and adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing behaviours? A study of Korean Adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 96, 213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep. 2008.03.007

-

Fletcher, D. & Sarkar, M. (2013). Psychological resilience A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. European Psychologist, 18 (1), 12-23. DOI: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000124

-

Richardson, G. E., Neiger, B. L., Jensen, S. & Kumpfer, K. L. (1990). The Resiliency Model. Health Education, 1990, 21, 33-39.

-

Coulter, T. J., Mallett, C. J., & Gucciardi, D. F. (2010) Understanding mental toughness in Australian soccer: Perceptions of players, parents, and coaches. Journal of Sports Sciences, 28 (7), 699-716. DOI: 10.1080/02640411003734085

-

White, R., & Bennie, A. (2015). Resilience in youth sport: A qualitative investigation of gymnastics coach and athlete perceptions. International Journal of Sport Science & Coaching, 10 (2+3). 379-393.

-

Sarkar, M., & Fletcher, D. (2014). Psychological resilience in sport performance: a review of stressors and protective factors. Journal of Sport Science, 15. 1419‐

-

Hays, K., Maynard, I., Thomas, O., & Bawden, M. (2007). Sources and Types of Confidence Identified by World Class Sport Performers. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 19, 434-456.

-

Gould, D., Dieffenbach, K., & Moffett, A. (2002). Psychological characteristics and their development in Olympic champions. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 14, 172-204. doi:10.1080/10413200290103482.

-

Holt, N. L., & Dunn, J. G. H. (2004). Toward a grounded theory of the psychosocial competencies and environmental conditions associated with football success. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 16, 199–219.

-

Gould, D., Hodge, K., Peterson, K., & Petlichkoff, L (1987). Psychological foundations of coaching: Similarities and differences among intercollegiate wrestling coaches. The Sport Psychologist, 1, 293 –308.

-

Weinberg, R., Butt, J., & Culp, B. (2011) Coaches’ views of mental toughness and how it is built. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 9 (2), 156-172, DOI: 10.1080/1612197X.2011.567106

-

Côté, J., Salmela, J. H., & Russell, S. (1995). The Knowledge of High-Performance Gymnastic Coaches: Competition and Training Considerations. The Sport Psychologist, 9, 76-95.

-

Morgan, P. B., C., Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2013). Defining and characterising team resilience in elite sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14. 549-559. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.01.004

-

Morgan, P., B., C., Fletcher, D. & Sarkar, M. (2019). Developing team resilience: A season-long study of psychosocial enablers and strategies in a high-level sports team. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.101543

-

Johns, A., Grossman, M., & McDonald, K. (2014). “More than a game”: The impact of sport-based youth mentoring schemes on developing resilience toward violent extremism. Social Inclusion, 2 (2), 57-70.

-

Sorkkila, M., Tolvanen, A., Aunola, K., & Ryba, T. V. (2019). The role of resilience in student-athletes’ sport and school burnout and dropout: A longitudinal person-oriented study. Scandinavian Journal of Medical Science Sports, 29. 1059-1067. DOI: 10.1111/sms.13422

-

Tabei, Y., Fletcher, D., & Goodger, K. (2012). The relationship between organizational stressors and athlete burnout in soccer players. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 6, 146–165.

-

Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2016) Mental fortitude training: An evidenced based approach to developing psychological resilience for sustained success. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 7 (3), 135-157. DOI: 10.1080/21520704.2016.1255496

-

Thelwell, R., Greenlees, L., & Weston, N. (2010). Examining the use of psychological skills throughout soccer performance. Journal of Sport Behavior, 33, 109–126.

-

Phelps & Abrahamson 08, pp4-5 – in Howells Fletcher 15 Phelps, M., & Abrahamson, A. (2008). No limits: The will to succeed. London, UK: Simon & Schuster.

-

Lazarus, R. S. (1966). Psychological stress and the coping process. New York: McGraw-Hill.

-

Lazarus, R. S. (1981). The stress and coping paradigm. In C. Eisdorfer, D. Cohen, A. Kleinman, & P. Maxim (Eds.), Models for clinical psychopathology (pp. 177–214). New York: Spectrum.

-

Madrigal, L. (2019) Developing mental toughness: Perspectives from NCAA Division I team sport coaches. Journal for the Study of Sports and Athletes in Education, 13 (3), 235-252, DOI: 10.1080/19357397.2019.1669366

-

Ungar, M., Brown, M., Liebenberg, L., Othman, R., Kwong, W.M., Armstrong, M., & Gilgun, J. (2007). Unique Pathways to Resilience Across Cultures. Adolescence, 42, 287-310.

-

Mageau, G., & Vallerand, R. (2003). The coach-athlete relationship: A motivational model. Journal of Sport Sciences, 21, 883–904.

-

Weinberg, R., Freysinger, V., & Mellano, K. (2018) How can coaches build mental toughness? Views from sport psychologists. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 9 (1). 1-10, DOI: 10.1080/21520704.2016.1263981

-

Fraser-Thomas, J. L., & Côté, J. (2009). Understanding Adolescents’ Positive and Negative Developmental Experiences in Sport. The Sport Psychologist, 23, 3-23.

-

Weinberg, R., & Gould, D. (2016). Foundations of sport and exercise psychology (6th ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

-

Olympiou, A., Jowett, S., & Duda, J.L. (2008). The Psychological Interface Between the Coach-Created Motivational Climate and the Coach-Athlete Relationship in Team Sports. The Sport Psychologist, 22, 423-438.

-

Hall, N. (2011). “Give It Everything You Got”: Resilience for Young Males Through Sport. International Journal of Men’s Health, 10, 65-81.

-

Visek, A. J., Harris, B. S., & Blom, L. C. (2013) Mental Training with Youth Sport Teams: Developmental Considerations and Best Practice Recommendations. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 4 (1), 45-55, DOI: 10.1080/21520704.2012.733910

-

Ames, C. (1992). Achievement goals, motivational climate, and motivational processes. In G. C. Roberts (Ed.), Motivation in sport and exercise (pp. 161–176). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

-

Vitali, F., Bortoli, L., Bertinato, L., Robazza, C., & Schena, F. (2015). Motivational climate, resilience, and burnout in youth sport. Sport Science Health, 11. 103-108. DOI 10.1007/s11332-014-0214-9

-

Epstein, J. (1989). Family structures and student motivation: A developmental perspective. In R. Ames (Eds.), Research on Motivation in Education (pp. 259-295). Academic Press: New York.